Research

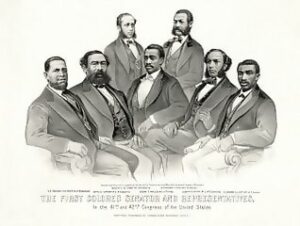

Blacks and whites both made enormous sacrifices and contributions to help build this nation. Learning this true history promotes a sense of pride and accomplishment, forging a connection to our common roots that heals and binds us together in a common cause for understanding, fairness, and equality.

Bryce-LaPorte further supports Black Studies on the basis that mutual respect for Afro-Americans must come through increased knowledge of their contributions to American culture.

However, Devlin (1970) remarks that the rewriting of American history to give the Negro his rightful place is overdue.

All youth struggle with their identities during their adolescent years. However, African Americans are faced with added social character challenges, such as having to deal with the notion that society does not think they can become high achievers. There are also significant, proven inequalities that come from being black.

Racial identity can impact the self-esteem of a child both while they are developing and throughout their lifetimes. Swanson, Cunningham, Youngblood II, and Spencer discussed the fact that children who were taught at a young age about their racial identity were less likely to feel a difference between their personal and group identity.

Stearns (1998) stated that history motivates and instills habits of mind that are essential for responsible public behavior, whether as a community or national leader, a petitioner, an informed voter, or a simple observer.

Harper (1977) argued that, in general, a traditional curriculum forces the black student to alienate himself and to psychologically or physically drop out of the regular school curriculum, thus many times seeking to satisfy his needs in unhealthy ways that can victimize himself and others.

Sources

Ford, D. Y., & Moore III, J. L. (2005). This issue: Gifted education. Theory into Practice, 44(2), 77-79. Retrieved from This Issue: Gifted Education

Harper, F. D. (1977). Developing a curriculum of self-esteem for Black youth. The Journal of Negro Education, 46(2), 133-140. Accessed: 29-07-2019 23:22 UTC.